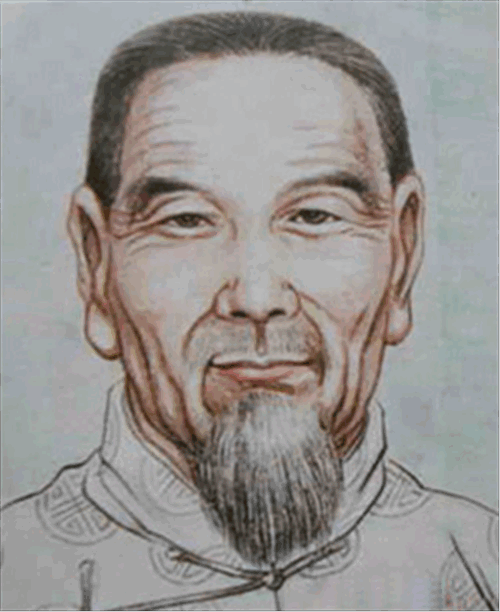

From Medicine Shop Handyman to Imperial Patriarch: The Legend of Yang Lu Chan’s Taijiquan

In 1799, a boy was born in a poor farmer’s house in Yongnian County, Hebei Province, and his parents named him Yang Fukui. This young man, who used to practise boxing in the fields on a hungry stomach, would shake Beijing forty years later with the name ‘Yang Wufu’, but his life took a turn for the worse when he started in an inconspicuous traditional Chinese medicine shop.

Behind the Medicine Cabinet

At the age of 15, Yang Lu Chan worked as a labourer in a medicine shop called ‘Taihe Tang’ on Xiguan Street in Guangping Prefecture. The owner of the pharmacy, Chen Dehu, was from Chenjiagou in Henan Province, a small village famous for its secret martial arts. Every morning when he wiped down the medicine cabinet, the boy was attracted by a special sound in the backyard: Master Chen Changxing was instructing his disciples to practice taijiquan, a form of martial arts whose seemingly slow movements contained the power to knock down a strong man.

Over the next six years, Yang Luchan developed a unique learning method: observing the moves while cleaning the courtyard, using a charcoal pencil to record the main points of the movements on the medicine wrapping paper, and trying to figure out the techniques of power between the sacks piled up in the warehouse. Seven pairs of sweat-soaked straw shoes were worn out in return for precise mastery of core moves such as the ‘Lazy Tie Yi’ and ‘Single Whip’.

Breaking the centuries-old rules of discipleship

In the late autumn of 1820, in the early hours of the morning, Chen Changxing discovered something unusual during his inspection – a figure was practising against the diagrams on the wall under the faint light from the storehouse. The water on the ground reflected the trajectory of the boxing technique, which matched perfectly with the rhythm of the Chen family’s secret breathing.

Three days later, the owner of the pharmacy, Chen Dehu, received a special request. According to the Chen family’s ancestral motto of ‘boxing not to be passed on to outsiders’, this should have been the moment to severely punish those who stole from the school. But in the face of Yang Lu Chan’s six-year compilation of three large practice notes and calluses on his hands, the two elders made a decision that would change the history of martial arts: to make an exception and accept him as Chen Chang Xing’s first disciple with a foreign surname.

Eighteen Years on the Road to Refinement

Formal apprenticeship opened up a more demanding training cycle:

First visit to Chenjiagou (1821-1825): mastered the 108 Chen-style Laojia Forms, repeating a single form more than 300 times a day.

The second Chenjiagou (1830-1835): studied Taiji spears, spring and autumn swords and other equipment, created the ‘sticky pole’ sparring method

Third Chenjiagou (1840-1842): He integrated the meridian and collateral theory of traditional Chinese medicine and established the internal gong method of ‘guiding qi with intention’.

By the time he left the school at the age of 44, he had already established his own style of boxing. Onlookers described his style as ‘like cotton wrapped in iron’, able to instantly disintegrate the opponent’s centre of gravity in a gentle push, a trait that would later become the hallmark of Yang Style Taijiquan.

In 1850, at the Rui Wang Fu martial arts stadium in Beijing, a competition was changing people’s perception of martial arts. Faced with the Mongolian wrestling champion’s swift pouncing, Yang Lu Chan sidestepped and lightly pressed his elbow, and the 200kg strong man even fell down unbalanced. This ‘four-two-thousand-kilogram’ technique, so that the ‘Yang invincible’ name spread throughout the eight banners military camps.

In the next twenty years, his student list covered the core of power in the Qing Dynasty:

Twenty-seven members of the royal family learnt the systematic health regimen.

Regular tactical training for the Eight Banner Army’s instructor corps.

The first ‘elevated’ model adapted to the robes of the nobility.

A revolution in martial arts that affected the world

By the time of his death in 1872, the Master’s innovations went beyond martial arts:

Safety Improvement: Replaced aerial kicking with ground training, reducing serious injuries by 89%.

System construction: Establishment of junior, intermediate and senior level courses, and supporting assessment and promotion system.

Cultural output: inspired modern film and television creations, his ‘Stealing Fist’ experience has been adapted into ‘Stealing Fist’ and other 12 films.

Nowadays, Yang Lu Chan’s ‘Thirteen Forms for Health’ is still the basic course of Taijiquan in the world. A study by New York University in 2023 showed that when the routine was practised consistently for six months, the risk of falling was reduced by 41% in middle-aged and elderly practitioners. From drugstore warehouse thief to multinational fitness programme founder, the legacy of this martial arts master is still being written.